Blood test results revealing low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) values can provide crucial insights into underlying health conditions affecting red blood cell production and function. These parameters, routinely measured as part of a complete blood count (CBC), serve as essential diagnostic markers for various haematological disorders, most commonly iron deficiency anaemia and thalassaemia syndromes. Understanding the clinical significance of reduced MCV and MCH levels enables healthcare professionals to identify microcytic hypochromic anaemia patterns and guide appropriate investigative pathways for optimal patient management.

Understanding mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) parameters

Mean corpuscular volume represents the average volume of individual red blood cells within a blood sample, expressed in femtolitres (fL). This parameter reflects the size characteristics of erythrocytes, providing valuable information about red blood cell morphology and maturation processes. When MCV values fall below normal ranges, it indicates the presence of microcytic red blood cells, which are characteristically smaller than typical healthy erythrocytes.

Mean corpuscular haemoglobin quantifies the average mass of haemoglobin contained within each red blood cell, measured in picograms (pg). MCH values directly correlate with the oxygen-carrying capacity of individual erythrocytes, as haemoglobin serves as the primary oxygen transport protein. Reduced MCH levels suggest diminished haemoglobin content per cell, often resulting in compromised oxygen delivery to peripheral tissues.

Normal reference ranges for MCV and MCH in adult populations

Established reference ranges for MCV in healthy adults typically span from 80 to 100 femtolitres, with slight variations depending on laboratory methodologies and demographic factors. Values below 80 fL are classified as microcytic, while measurements exceeding 100 fL indicate macrocytic red blood cells. Age-related changes can influence MCV ranges, with elderly populations sometimes demonstrating slightly elevated baseline values.

MCH reference ranges generally fall between 27 and 33 picograms in adult populations, though laboratory-specific variations may occur. Values below 27 pg typically indicate hypochromic anaemia , characterised by reduced haemoglobin concentration within red blood cells. These standardised ranges enable clinicians to identify abnormal red blood cell indices and initiate appropriate diagnostic investigations.

Laboratory measurement techniques using automated haematology analysers

Modern automated haematology analysers employ sophisticated technologies to determine MCV and MCH values with exceptional precision and reproducibility. These instruments utilise electrical impedance methods, flow cytometry, or light scatter techniques to measure individual cell characteristics within blood samples. Advanced analysers can process thousands of cells per sample, providing statistically robust measurements that minimise sampling errors.

Quality control measures ensure analytical accuracy through regular calibration procedures and participation in external quality assurance programmes. Standardised sample preparation protocols maintain consistency across different laboratory settings, enabling reliable comparison of results between healthcare facilities. These technological advances have revolutionised haematological diagnostics, providing rapid and accurate assessment of red blood cell parameters.

Coulter principle and flow cytometry applications in red blood cell analysis

The Coulter principle, based on electrical impedance measurement, remains a fundamental technology for determining cell volume in many haematology analysers. As red blood cells pass through a small aperture between electrodes, they displace electrolyte solution, causing measurable changes in electrical resistance proportional to cell volume. This technique provides direct MCV measurements with excellent reproducibility and precision.

Flow cytometry applications offer alternative approaches for red blood cell analysis, utilising laser light scattering properties to determine cell size and internal complexity. These methods can simultaneously measure multiple cellular parameters, providing comprehensive red blood cell characterisation beyond basic volume measurements. Advanced flow cytometry systems can detect subtle morphological abnormalities that may not be apparent through conventional impedance-based methods.

Clinical significance of combined low MCV and MCH results

The simultaneous occurrence of low MCV and MCH values creates a distinctive pattern known as microcytic hypochromic anaemia, which significantly narrows the differential diagnosis. This combination suggests impaired haemoglobin synthesis or inadequate iron availability for erythropoiesis, directing clinical attention towards specific underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. The severity of reduction in both parameters often correlates with the degree of underlying disease progression.

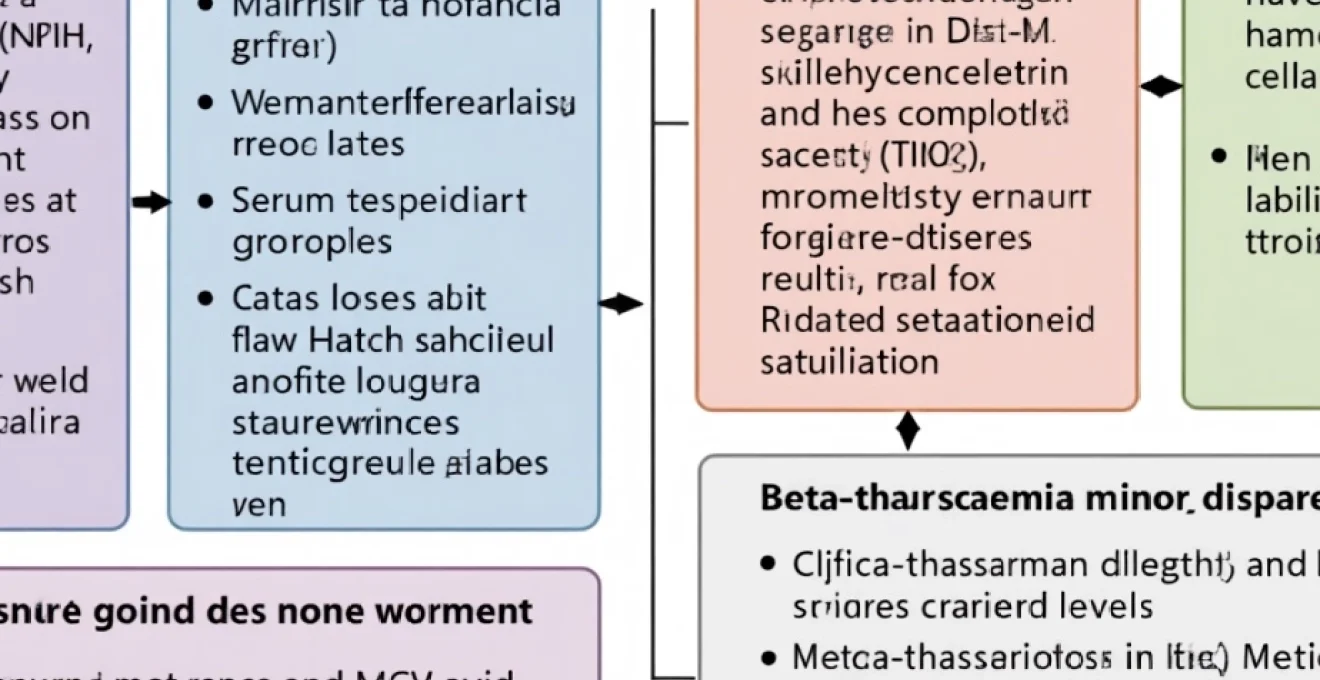

Diagnostic algorithms typically prioritise iron deficiency anaemia investigation when confronted with combined low MCV and MCH values, given its prevalence in clinical practice. However, comprehensive evaluation must consider alternative causes including thalassaemia traits, chronic inflammatory conditions, and lead toxicity. The pattern recognition approach enables efficient diagnostic workups while avoiding unnecessary testing procedures.

Iron deficiency anaemia as primary cause of microcytic hypochromic red blood cells

Iron deficiency anaemia represents the most common cause of combined low MCV and MCH values worldwide, affecting approximately 25% of the global population according to recent epidemiological studies. This condition develops through progressive iron depletion stages, beginning with reduced iron stores and ultimately resulting in insufficient iron availability for haemoglobin synthesis. The characteristic microcytic hypochromic red blood cell morphology reflects the body’s attempt to maintain red blood cell production despite inadequate iron resources.

The pathophysiology involves disrupted haem synthesis pathways, where iron serves as an essential cofactor for haemoglobin production. When iron availability becomes limiting, newly formed red blood cells contain reduced haemoglobin concentrations and exhibit smaller cell volumes. Progressive iron depletion leads to increasingly severe microcytosis and hypochromia , creating the distinctive laboratory pattern observed in established iron deficiency anaemia.

Clinical manifestations typically develop gradually, allowing physiological adaptation mechanisms to partially compensate for reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. Early symptoms may include fatigue, weakness, and reduced exercise tolerance, progressing to more severe manifestations such as dyspnoea, palpitations, and cognitive impairment in advanced cases. The insidious onset often delays diagnosis, emphasising the importance of routine laboratory screening in at-risk populations.

Serum ferritin and transferrin saturation diagnostic markers

Serum ferritin serves as the primary biomarker for assessing body iron stores, with concentrations below 15 μg/L in women and 20 μg/L in men indicating iron deficiency. However, ferritin acts as an acute phase reactant, potentially masking iron deficiency in patients with concurrent inflammatory conditions. Elevated ferritin levels may occur despite iron deficiency when inflammatory processes are present, complicating diagnostic interpretation.

Transferrin saturation, calculated as the ratio of serum iron to total iron-binding capacity, provides additional diagnostic information about iron availability for erythropoiesis. Values below 16% typically indicate functional iron deficiency, even when ferritin levels remain within normal ranges. This parameter proves particularly valuable in distinguishing iron deficiency from anaemia of chronic disease, where transferrin saturation remains low but ferritin levels are elevated.

Total Iron-Binding capacity (TIBC) and soluble transferrin receptor levels

Total iron-binding capacity reflects the maximum amount of iron that can be bound by transferrin in serum, typically increasing in iron deficiency states as the body attempts to enhance iron absorption and transport. Elevated TIBC values above 450 μg/dL suggest iron deficiency, particularly when combined with low serum iron concentrations. This inverse relationship between iron availability and binding capacity provides valuable diagnostic insights.

Soluble transferrin receptor levels offer an inflammation-independent marker of tissue iron deficiency, making it particularly useful in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions. Elevated soluble transferrin receptor concentrations reflect increased cellular iron requirements and provide reliable evidence of functional iron deficiency. The transferrin receptor-ferritin index combines these parameters to improve diagnostic accuracy in complex clinical scenarios.

Gastrointestinal blood loss and Menorrhagia-Related iron depletion

Gastrointestinal bleeding represents a significant cause of iron deficiency in adult populations, with potential sources including peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel conditions, colorectal malignancies, and vascular malformations. Chronic occult bleeding may not produce obvious clinical signs, making laboratory detection of iron deficiency the first indication of underlying pathology. Comprehensive gastrointestinal evaluation becomes essential when iron deficiency is identified in post-menopausal women or adult men.

Menorrhagia affects approximately 20% of reproductive-age women, creating substantial iron losses that exceed dietary intake capacity in many cases. Monthly menstrual blood loss exceeding 80 mL can rapidly deplete iron stores, particularly in women with marginal dietary iron intake. The cyclical nature of menstrual iron losses requires ongoing monitoring and often necessitates iron supplementation to maintain adequate stores.

Dietary iron absorption disorders and coeliac disease associations

Dietary iron exists in two forms: haem iron from animal sources and non-haem iron from plant-based foods. Haem iron demonstrates superior bioavailability, with absorption rates of 15-25% compared to 2-5% for non-haem iron. Vegetarian and vegan diets may predispose individuals to iron deficiency, particularly when combined with increased iron requirements during pregnancy or periods of rapid growth.

Coeliac disease affects approximately 1% of the population and frequently presents with iron deficiency anaemia as the sole manifestation, even in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms. Villous atrophy in the duodenum impairs iron absorption, leading to progressive iron depletion despite adequate dietary intake. Iron deficiency anaemia may precede other coeliac disease manifestations by years , highlighting the importance of coeliac serology testing in patients with unexplained iron deficiency.

Thalassaemia syndromes and haemoglobinopathy differential diagnosis

Thalassaemia syndromes constitute inherited disorders characterised by reduced synthesis of specific globin chains, resulting in microcytic hypochromic red blood cells that may mimic iron deficiency anaemia. These conditions affect millions of people worldwide, with particularly high prevalence rates in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian populations. The genetic basis involves mutations affecting α-globin or β-globin gene clusters, leading to imbalanced globin chain production and ineffective erythropoiesis.

Distinguishing thalassaemia traits from iron deficiency anaemia requires careful evaluation of multiple parameters, as both conditions produce similar MCV and MCH reductions. However, thalassaemia carriers typically maintain normal or elevated red blood cell counts despite microcytosis, contrasting with the reduced red blood cell counts observed in iron deficiency. Family history and ethnic background provide important diagnostic clues that should prompt specific genetic testing when appropriate.

The clinical significance of thalassaemia trait recognition extends beyond individual diagnosis to include genetic counselling and family screening. Couples carrying thalassaemia mutations face risks of having children with severe thalassaemia major, requiring lifelong transfusion therapy and iron chelation treatment. Early identification enables informed reproductive decisions and appropriate prenatal diagnostic options.

Alpha-thalassaemia trait and HbH disease manifestations

Alpha-thalassaemia results from deletions or mutations affecting the four α-globin genes located on chromosome 16. Silent carriers with single gene deletions typically show normal haematological parameters, while α-thalassaemia trait (two gene deletions) produces mild microcytic anaemia with preserved red blood cell counts. The severity correlates with the number of affected genes, ranging from asymptomatic carriership to severe hydrops fetalis in cases with four gene deletions.

HbH disease occurs when three of the four α-globin genes are affected, resulting in moderate to severe anaemia with distinctive red blood cell morphology. HbH inclusions form within red blood cells due to excess β-globin chain precipitation, creating characteristic cellular abnormalities visible on supravital staining. These patients typically require regular monitoring and may need occasional blood transfusions during periods of increased physiological stress.

Beta-thalassaemia minor and intermedia classification systems

Beta-thalassaemia minor, resulting from mutations affecting one of the two β-globin genes, typically produces mild microcytic anaemia with elevated HbA2 levels on haemoglobin electrophoresis. These individuals usually remain asymptomatic but demonstrate persistent microcytosis that may be mistaken for iron deficiency. The characteristic laboratory pattern includes disproportionately low MCV relative to the degree of anaemia, often described as a high red blood cell count with low MCV.

Beta-thalassaemia intermedia encompasses a spectrum of conditions with variable clinical severity, ranging from mild anaemia requiring minimal intervention to moderate disease necessitating regular transfusions. Genetic modifiers and coinheritance of other haemoglobin variants influence the clinical phenotype, creating diverse presentations within this category. Understanding these variations helps guide appropriate management strategies and genetic counselling approaches.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis and High-Performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

Haemoglobin electrophoresis separates different haemoglobin variants based on their electrical charge properties, enabling identification of abnormal haemoglobin types characteristic of thalassaemia syndromes. Elevated HbA2 levels above 3.5% typically indicate β-thalassaemia trait, while increased HbF concentrations may suggest various thalassaemia variants. The technique provides qualitative and quantitative analysis of haemoglobin fractions essential for accurate diagnosis.

High-performance liquid chromatography offers superior resolution and precision compared to traditional electrophoresis methods, enabling detection of subtle haemoglobin variants that might be missed by conventional techniques. Automated HPLC systems provide rapid, standardised analysis with excellent reproducibility, making them ideal for routine screening programmes in high-prevalence populations. The technology has revolutionised thalassaemia diagnosis by improving detection sensitivity and reducing analytical turnaround times.

Mentzer index and Shine-Lal index calculations for thalassaemia screening

The Mentzer index, calculated as MCV divided by red blood cell count, provides a simple screening tool for distinguishing iron deficiency from thalassaemia trait. Values below 13 suggest thalassaemia, while indices above 13 indicate iron deficiency with reasonable accuracy. However, this discriminant function shows limitations in borderline cases and populations with mixed deficiencies, requiring confirmation through additional testing methods.

The Shine-Lal index incorporates MCV, MCH, and red blood cell count in the formula (MCV × MCV × MCH)/100, with values below 1530 suggesting thalassaemia trait. Multiple discriminant indices improve diagnostic accuracy when used in combination, though none achieve perfect sensitivity and specificity. These screening tools prove most valuable in resource-limited settings where comprehensive laboratory testing may not be readily available.

Chronic Disease-Associated anaemia and inflammatory cytokine effects

Chronic disease-associated anaemia, previously known as anaemia of chronic inflammation, represents the second most common cause of anaemia worldwide after iron deficiency. This condition develops in patients with prolonged inflammatory states, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease, and malignancies. The underlying pathophysiology involves complex interactions between inflammatory cytokines, iron metabolism, and erythropoiesis, ultimately resulting in reduced red blood cell production and shortened red blood cell survival.

Inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ, disrupt normal iron homeostasis by increasing hepcidin production in hepatocytes. Elevated hepcidin levels block iron release from macrophages and enterocytes , creating functional iron deficiency despite adequate total body iron stores. This mechanism explains why patients with chronic inflammatory conditions may develop microcytic anaemia resembling iron deficiency, even when ferritin levels remain elevated.

The anaemia typically develops gradually over weeks to months, allowing physiological adaptation that may mask clinical symptoms until the condition becomes severe. Laboratory findings often reveal mild to moderate microcytosis with low transferrin saturation but normal or elevated ferritin levels. The combination of inflammatory markers (elevated C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) with these iron parameters helps distinguish chronic disease anaemia from pure iron deficiency states.

Recent studies indicate that up to

30% of patients with chronic inflammatory conditions develop some degree of anaemia, with severity correlating directly to inflammatory activity levels and disease duration.

Lead poisoning and heavy metal toxicity impact on erythropoiesis

Lead poisoning represents a significant environmental health concern that profoundly affects haematopoiesis, particularly red blood cell production and haemoglobin synthesis. Chronic lead exposure interferes with multiple enzymatic steps in the haem biosynthetic pathway, most notably inhibiting δ-aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase and ferrochelatase activities. These enzymatic disruptions result in characteristic microcytic hypochromic anaemia with distinctive laboratory findings including elevated zinc protoporphyrin levels and basophilic stippling on peripheral blood smears.

The pathophysiology involves lead’s high affinity for sulfhydryl groups in critical enzymes, effectively blocking haem synthesis despite adequate iron availability. Additionally, lead exposure increases red blood cell membrane fragility and reduces erythrocyte lifespan, contributing to the anaemic state through enhanced haemolysis. Children demonstrate particular vulnerability to lead toxicity due to increased gastrointestinal absorption rates and developing nervous systems that are more susceptible to neurotoxic effects.

Occupational exposure sources include battery manufacturing, paint removal from older buildings, pottery glazing, and metal smelting operations. Environmental contamination from legacy lead-based paints, contaminated soil, and old plumbing systems continues to pose risks, particularly in urban areas with older housing stock. Blood lead levels above 10 μg/dL in children warrant immediate intervention and source identification to prevent permanent developmental consequences.

Diagnostic confirmation requires blood lead level measurement, with concurrent assessment of zinc protoporphyrin or free erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels. These metabolites accumulate when lead blocks the final step of haem synthesis, serving as biomarkers for both recent and chronic lead exposure. Chelation therapy becomes necessary for severely elevated blood lead levels, utilising agents such as succimer or calcium disodium EDTA under specialist supervision.

Clinical management strategies for microcytic hypochromic anaemia cases

Effective management of microcytic hypochromic anaemia requires a systematic diagnostic approach that identifies the underlying aetiology before initiating targeted therapeutic interventions. The initial assessment should encompass comprehensive history-taking focused on dietary habits, menstrual history, gastrointestinal symptoms, family background, and potential environmental exposures. Physical examination may reveal specific signs such as koilonychia, restless leg syndrome, or splenomegaly that provide diagnostic clues about the underlying cause.

Laboratory investigation follows a structured algorithm beginning with iron studies to assess iron deficiency, followed by haemoglobin electrophoresis or HPLC analysis when thalassaemia is suspected. Serum ferritin levels below 30 μg/L strongly suggest iron deficiency, though higher thresholds may apply in patients with concurrent inflammatory conditions. Additional testing may include coeliac serology, lead levels, or bone marrow examination in complex cases where initial investigations prove inconclusive.

Iron replacement therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment for confirmed iron deficiency anaemia, with oral ferrous sulfate representing the first-line approach in most patients. Standard dosing typically involves 65-130 mg of elemental iron daily, preferably taken between meals to optimise absorption. Common gastrointestinal side effects including nausea, constipation, and epigastric discomfort can be minimised through dose reduction or alternative iron formulations such as ferrous gluconate or iron polymaltose complexes.

Parenteral iron therapy becomes necessary when oral supplementation fails due to malabsorption, intolerance, or ongoing losses that exceed oral replacement capacity. Modern intravenous iron preparations including iron sucrose, ferric carboxymaltose, and iron isomaltoside offer excellent safety profiles with rapid iron repletion. Total iron deficit calculations guide appropriate dosing using formulas that incorporate patient weight, target haemoglobin levels, and estimated iron stores requirements.

Monitoring treatment response involves serial complete blood counts at 2-4 week intervals, expecting reticulocyte response within 7-10 days and haemoglobin improvement of 1-2 g/dL weekly with adequate therapy. Failure to respond appropriately suggests either inadequate dosing, continued losses, malabsorption, or alternative diagnoses requiring reassessment. Iron replacement should continue for 3-6 months after haemoglobin normalisation to replenish tissue iron stores and prevent early recurrence.

Dietary counselling plays a crucial supportive role, emphasising iron-rich foods including red meat, poultry, fish, legumes, and fortified cereals. Enhancers of iron absorption such as vitamin C should be recommended, while inhibitors including tea, coffee, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors require timing considerations. Vegetarian patients may need higher iron intake recommendations due to the lower bioavailability of non-haem iron sources predominant in plant-based diets.

Management of thalassaemia traits typically requires no specific treatment beyond genetic counselling and family screening. However, these patients should avoid unnecessary iron supplementation, which may lead to iron overload in the absence of true deficiency. Regular monitoring ensures clinical stability while genetic counselling addresses reproductive implications and prenatal diagnostic options for at-risk couples.

Chronic disease-associated anaemia management focuses primarily on treating the underlying inflammatory condition while considering targeted therapies for severe cases. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents may benefit selected patients with chronic kidney disease or cancer-related anaemia, though careful risk-benefit assessment is essential. Iron supplementation proves beneficial when functional iron deficiency coexists with inflammatory anaemia, often requiring parenteral administration for optimal efficacy.