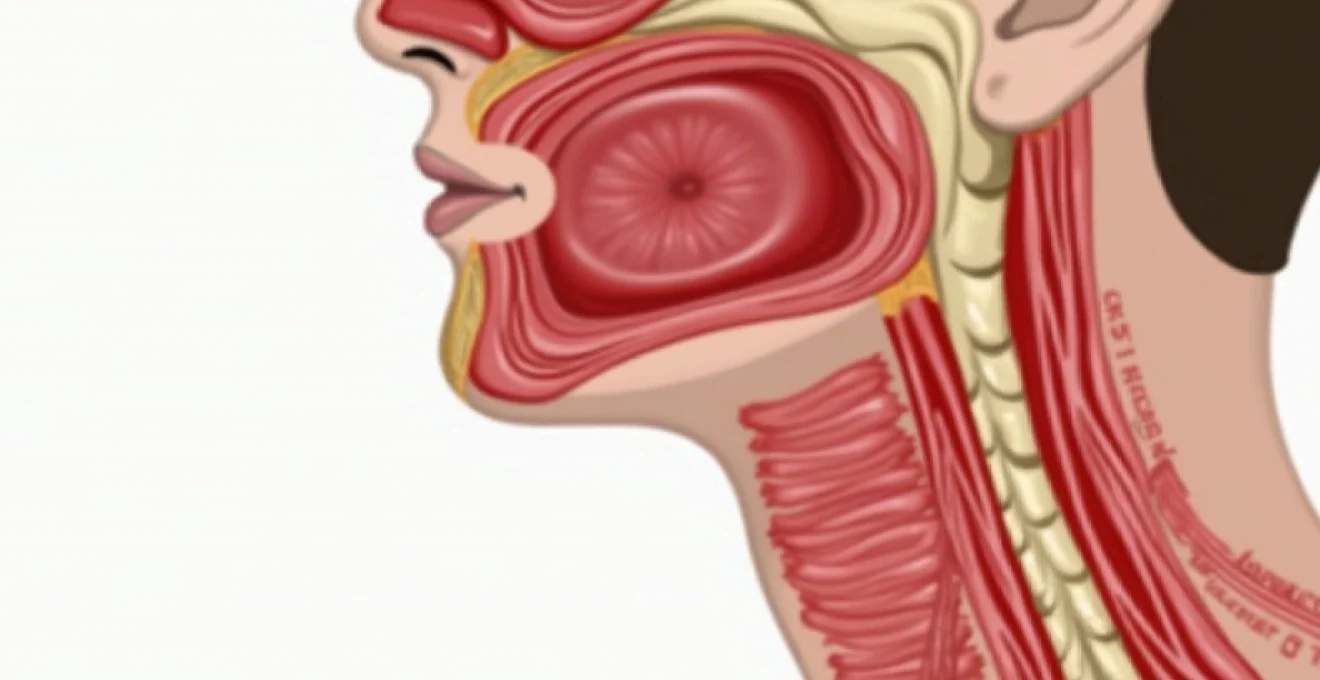

Pain in the front of the neck near the windpipe represents a complex symptom that can stem from various anatomical structures and pathological processes. This distinctive discomfort affects millions of individuals annually, ranging from mild irritation to severe, debilitating pain that interferes with basic functions such as swallowing, breathing, and speaking. The anterior cervical region houses critical structures including the trachea, thyroid gland, larynx, and surrounding soft tissues, each capable of generating pain that manifests in the front of the neck. Understanding the underlying causes requires careful consideration of the intricate anatomy and the diverse conditions that can affect this vital region of the human body.

Anatomical structure of the anterior cervical region and tracheal framework

The anterior neck region encompasses a sophisticated network of structures that work in harmonious coordination to facilitate breathing, swallowing, and vocal production. The windpipe, or trachea, serves as the central conduit for air passage, extending from the cricoid cartilage at approximately the sixth cervical vertebra to the bifurcation at the carina. This tubular structure measures roughly 10-12 centimetres in length and consists of 16-20 C-shaped cartilaginous rings that provide structural integrity while maintaining flexibility during neck movement.

Thyroid cartilage position and adam’s apple prominence

The thyroid cartilage forms the largest component of the laryngeal framework, creating the characteristic prominence known as the Adam’s apple. This V-shaped structure protects the vocal cords and creates the anterior boundary of the laryngeal cavity. The thyroid cartilage articulates with the cricoid cartilage below through the cricothyroid joint, allowing for pitch modulation during phonation. Inflammation or injury to this cartilage can produce localised pain that radiates throughout the anterior neck region, particularly during swallowing or voice production.

Cricoid cartilage ring and cricothyroid membrane location

The cricoid cartilage represents the only complete cartilaginous ring in the laryngeal framework, positioned just below the thyroid cartilage. This signet ring-shaped structure provides crucial support to the lower larynx and serves as the attachment point for several intrinsic laryngeal muscles. The cricothyroid membrane spans the space between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages, forming a readily palpable landmark that emergency medical professionals utilise for surgical airway access. Pathological processes affecting this region often manifest as sharp, localised pain during neck movement or deep inspiration.

Tracheal rings C-Shaped cartilage distribution

The tracheal cartilages consist of horseshoe-shaped rings that maintain airway patency while allowing for oesophageal expansion during swallowing. These incomplete rings feature gaps posteriorly, bridged by the trachealis muscle and fibrous membrane. The first tracheal ring sits immediately below the cricoid cartilage, with subsequent rings extending toward the thoracic inlet. Inflammatory conditions affecting these cartilaginous structures can generate diffuse anterior neck discomfort that intensifies with respiratory effort or external pressure application.

Sternocleidomastoid muscle attachment points

The sternocleidomastoid muscles create prominent anatomical landmarks on either side of the anterior neck, originating from the mastoid process and inserting on the sternum and clavicle. These powerful muscles facilitate head rotation and lateral flexion while serving as important surgical landmarks for cervical procedures. Muscular strain or inflammation in these structures can produce referred pain patterns that extend across the anterior neck region, often mimicking deeper pathological processes affecting the tracheal or laryngeal structures.

Infectious aetiologies affecting the anterior neck and windpipe region

Infectious processes represent one of the most common causes of anterior neck pain, ranging from superficial soft tissue infections to deep-seated abscesses that threaten airway integrity. These conditions often develop rapidly and require prompt recognition and treatment to prevent serious complications. The rich vascular supply and lymphatic drainage of the anterior neck region create an environment conducive to bacterial proliferation, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or following upper respiratory tract infections.

Acute bacterial tracheitis and staphylococcus aureus involvement

Acute bacterial tracheitis presents as a potentially life-threatening infection of the tracheal mucosa, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pneumoniae . This condition typically affects children between six months and six years of age, though adult cases occur with increasing frequency. Patients develop severe anterior neck pain accompanied by high fever, stridor, and productive cough with purulent sputum. The infection causes significant mucosal swelling and pseudomembrane formation, potentially leading to airway obstruction that requires immediate intervention.

Viral laryngotracheobronchitis and parainfluenza virus manifestations

Viral laryngotracheobronchitis, commonly known as croup, represents the most frequent cause of anterior neck discomfort in paediatric populations. Parainfluenza viruses account for approximately 65% of cases, though respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus also contribute to the clinical syndrome. The infection causes subglottic inflammation and swelling, producing the characteristic barking cough and inspiratory stridor. Patients experience anterior neck tenderness that worsens with coughing or crying, accompanied by low-grade fever and hoarse voice quality.

Epiglottitis secondary to haemophilus influenzae type B

Epiglottitis represents a medical emergency characterised by rapid-onset inflammation of the epiglottis and surrounding supraglottic structures. Although Haemophilus influenzae type B historically caused most cases, widespread vaccination has shifted the epidemiology toward Streptococcus pneumoniae , Staphylococcus aureus , and Haemophilus parainfluenzae . Patients develop severe anterior neck pain that intensifies with swallowing, accompanied by high fever, drooling, and the characteristic tripod positioning. The rapid progression from symptom onset to airway compromise necessitates immediate medical evaluation and potential airway intervention.

Retropharyngeal abscess formation and streptococcal aetiology

Retropharyngeal abscesses develop within the potential space between the pharynx and prevertebral fascia, most commonly following suppuration of retropharyngeal lymph nodes. Group A Streptococcus represents the predominant causative organism, though polymicrobial infections involving anaerobic bacteria increasingly occur in adult populations. Patients present with severe anterior neck pain that radiates to the ear, accompanied by fever, dysphagia, and characteristic neck hyperextension to optimise airway patency. The infection can extend into the mediastinum, creating a life-threatening complication known as descending necrotising mediastinitis.

Inflammatory and autoimmune conditions causing anterior cervical discomfort

Inflammatory and autoimmune conditions affecting the anterior neck region encompass a diverse spectrum of disorders that can produce chronic or recurrent pain patterns. These conditions often involve the thyroid gland, tracheal cartilage, or surrounding connective tissues, creating complex symptom presentations that challenge diagnostic accuracy. The inflammatory response triggers pain through multiple mechanisms, including direct tissue damage, nerve sensitisation, and mechanical compression of adjacent structures.

Subacute thyroiditis de quervain and viral trigger mechanisms

Subacute thyroiditis, also known as De Quervain’s thyroiditis or granulomatous thyroiditis, represents a self-limiting inflammatory condition that produces severe anterior neck pain. This condition typically follows viral upper respiratory tract infections, with Coxsackievirus , Epstein-Barr virus , and adenovirus implicated as potential triggers. Patients develop intense pain that radiates to the jaw, ear, and upper chest, often accompanied by fever, malaise, and palpitations. The thyroid gland becomes exquisitely tender to palpation, and laboratory studies reveal elevated inflammatory markers and characteristic thyroid function abnormalities.

The pain associated with subacute thyroiditis often represents one of the most severe forms of anterior neck discomfort, with many patients describing it as unbearable without appropriate anti-inflammatory treatment.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis lymphocytic infiltration patterns

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis constitutes the most common autoimmune thyroid disorder, characterised by progressive lymphocytic infiltration and destruction of thyroid follicles. While typically painless, some patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis experience chronic anterior neck discomfort, particularly during acute exacerbations. The inflammatory process involves molecular mimicry between thyroid antigens and infectious agents, leading to sustained autoimmune activation. Patients may develop a sensation of fullness or pressure in the anterior neck, accompanied by dysphagia and voice changes as the gland enlarges and compresses surrounding structures.

Relapsing polychondritis affecting tracheal cartilage

Relapsing polychondritis represents a rare systemic autoimmune disorder that specifically targets cartilaginous structures throughout the body. When affecting the tracheal cartilage, patients develop severe anterior neck pain accompanied by respiratory symptoms including dyspnoea, stridor, and chronic cough. The inflammatory process causes progressive destruction of the C-shaped tracheal rings, potentially leading to tracheomalacia and airway collapse. Episodes typically occur in a relapsing and remitting pattern , with acute flares producing intense pain that may be mistaken for infectious causes.

Acute suppurative thyroiditis bacterial seeding routes

Acute suppurative thyroiditis represents an uncommon but serious bacterial infection of the thyroid gland, typically occurring through haematogenous spread or direct extension from adjacent infections. The unique anatomy of the thyroid gland, with its rich blood supply and iodine content, generally provides protection against bacterial invasion. However, immunocompromised patients or those with pre-existing thyroid pathology may develop this life-threatening condition. Patients present with severe anterior neck pain, high fever, and signs of systemic toxicity, requiring immediate antimicrobial therapy and potential surgical drainage.

Neoplastic processes and malignant transformations in the anterior neck

Neoplastic processes affecting the anterior neck region encompass both benign and malignant tumours that can produce pain through various mechanisms including mass effect, tissue infiltration, and inflammatory responses. The anatomical complexity of this region means that tumours can arise from multiple tissue types, including epithelial, mesenchymal, lymphoid, and neural elements. Early recognition of malignant processes remains crucial for optimal treatment outcomes, as many cancers affecting the anterior neck region demonstrate aggressive biological behaviour with potential for rapid local invasion and distant metastasis.

Thyroid carcinomas represent the most common malignant tumours of the anterior neck, with papillary thyroid carcinoma accounting for approximately 85% of cases. While most thyroid cancers remain asymptomatic in early stages, larger tumours or those with extrathyroidal extension can produce anterior neck pain through compression or invasion of surrounding structures. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, though rare, demonstrates particularly aggressive behaviour with rapid growth and early symptoms including severe neck pain, dysphagia, and voice changes. The pain associated with thyroid malignancies often develops gradually but may become severe as the tumour invades the trachea, oesophagus, or recurrent laryngeal nerves.

Laryngeal carcinomas frequently present with anterior neck discomfort, particularly when involving the supraglottic or subglottic regions. Squamous cell carcinoma comprises over 95% of laryngeal malignancies, with strong associations to tobacco use and alcohol consumption. Patients typically develop progressive hoarseness accompanied by anterior neck pain that worsens with swallowing or speaking. Advanced tumours may cause referred otalgia through involvement of the vagus nerve, creating a complex pain pattern that extends beyond the immediate tumour location. The pain often intensifies as the tumour erodes through cartilaginous structures or invades surrounding soft tissues.

Primary tracheal malignancies remain exceedingly rare, accounting for less than 0.1% of all cancers, but can produce significant anterior neck pain when present. Adenoid cystic carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma represent the most common histological subtypes, with adenoid cystic tumours demonstrating a propensity for perineural invasion that can produce severe pain disproportionate to tumour size. The cylindrical anatomy of the trachea means that even small tumours can cause significant symptoms including dyspnoea, stridor, and anterior neck pain that intensifies with respiratory effort. Secondary involvement of the trachea by adjacent malignancies, particularly thyroid or oesophageal cancers, occurs more frequently and can produce similar pain patterns through direct invasion or external compression.

The development of new, persistent anterior neck pain in individuals over 50 years of age, particularly those with risk factors such as smoking or previous radiation exposure, warrants thorough evaluation to exclude malignant processes.

Trauma-related injuries and mechanical causes of windpipe pain

Traumatic injuries to the anterior neck region can produce immediate or delayed onset of pain through various mechanisms including direct tissue damage, haematoma formation, and disruption of normal anatomical relationships. The windpipe and surrounding structures are particularly vulnerable to both blunt and penetrating trauma due to their superficial location and limited bony protection. Understanding the patterns of injury and their associated pain presentations is crucial for appropriate triage and management of trauma patients.

Blunt cervical trauma commonly occurs in motor vehicle accidents, sports injuries, and assault cases, with the mechanism of injury determining the pattern of structural damage. Hyperextension injuries can cause disruption of the anterior longitudinal ligament and compression of posterior structures, while hyperflexion mechanisms may damage the posterior ligamentous complex and compress anterior elements. The pain following blunt cervical trauma often develops gradually as inflammatory responses evolve, with patients experiencing stiffness, muscle spasm, and referred pain patterns that can extend throughout the anterior and posterior neck regions. Delayed onset of symptoms is particularly concerning as it may indicate progressive haematoma formation or developing instability.

Penetrating neck injuries present immediate life-threatening concerns due to the concentration of vital structures within the cervical region. The anterior triangle of the neck contains the carotid arteries, jugular veins, trachea, oesophagus, and numerous nerves, making penetrating injuries potentially catastrophic. Pain associated with penetrating trauma may be overshadowed by more immediate concerns such as airway compromise or vascular injury, but patients who survive the initial insult often develop significant anterior neck pain as healing progresses. The inflammatory response to tissue damage, combined with surgical interventions often required for repair, can create complex pain syndromes that persist long after the initial injury.

Iatrogenic trauma from medical procedures represents an increasingly recognised cause of anterior neck pain, particularly with the growing use of minimally invasive surgical techniques. Endotracheal intubation, central venous catheterisation, and thyroid surgery all carry risks of inadvertent injury to surrounding structures. Post-intubation throat pain is extremely common, affecting up to 90% of patients following general anaesthesia, though most cases resolve within 24-48 hours. More serious complications such as laryngeal nerve injury or tracheal perforation can produce persistent anterior neck pain that may require additional intervention.

Mechanical causes of anterior neck pain include muscular strain, ligamentous injury, and cervical spine dysfunction that refers pain to the anterior region. The complex interplay between cervical facet joints, intervertebral discs, and myofascial structures creates multiple potential sources of referred pain. Whiplash-associated disorders commonly produce anterior neck pain through this mechanism, with patients developing symptoms that may not correlate directly with imaging findings. The pain often fluctuates with neck position and movement, responding variably to conservative management approaches including physiotherapy, manipulation, and pharmacological intervention.

Gastroesophageal and laryngopharyngeal reflux manifestations

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) represent increasingly recognised causes of anterior neck discomfort that can mimic more serious pathological processes. These conditions involve the retrograde flow of gastric contents into the oesophagus and, in the case of LPR, the larynx and pharynx. The acidic nature of gastric

contents causes irritation and inflammation of the mucosal surfaces, leading to pain that patients often describe as burning, aching, or pressure-like sensations in the anterior neck region. The prevalence of reflux-related anterior neck symptoms has increased dramatically over the past two decades, paralleling the rising incidence of obesity, dietary changes, and lifestyle factors that predispose individuals to gastric acid dysfunction.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease affects approximately 20% of the Western population, with a significant subset experiencing extraesophageal manifestations including anterior neck pain. The pathophysiology involves failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to maintain adequate pressure gradients, allowing gastric contents to migrate proximally. When acidic material reaches the upper esophagus and hypopharynx, it triggers inflammatory cascades that affect the laryngeal framework and surrounding tissues. Patients typically experience anterior neck discomfort that worsens after meals, when lying flat, or during periods of increased intra-abdominal pressure. The pain may be accompanied by globus sensation, chronic throat clearing, and voice changes that can persist for hours after reflux episodes.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux represents a distinct clinical entity where gastric contents reach the larynx and pharynx, causing direct mucosal injury and inflammatory responses. Unlike traditional GERD, LPR patients may not experience classic heartburn symptoms, making diagnosis challenging and often delayed. The laryngeal tissues demonstrate exquisite sensitivity to acid exposure, with pH levels below 4.0 causing immediate inflammatory responses and tissue damage. Patients with LPR often describe a sensation of something stuck in their throat, accompanied by anterior neck pain that intensifies with voice use or swallowing. The chronic inflammation can lead to laryngeal edema, vocal cord granulomas, and posterior laryngitis that produces persistent anterior neck discomfort.

The diagnostic approach to reflux-related anterior neck pain requires comprehensive evaluation including symptom assessment, laryngoscopy, and potentially ambulatory pH monitoring. Physical examination may reveal erythema and edema of the posterior larynx, arytenoid cartilages, and true vocal cords. The Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) provide standardised tools for quantifying symptom severity and laryngeal findings. Treatment typically involves proton pump inhibitor therapy for 3-6 months, combined with lifestyle modifications including dietary changes, weight reduction, and elevation of the head of the bed. Response to treatment can be variable, with some patients requiring extended therapy or additional interventions such as fundoplication for symptom resolution.

The connection between reflux disease and anterior neck pain is often overlooked in clinical practice, leading to unnecessary investigations and inappropriate treatments for patients with this common but underrecognised condition.

Pepsin, the proteolytic enzyme from gastric juice, plays a crucial role in laryngopharyngeal tissue damage even in the absence of acid. This enzyme remains stable in the laryngeal environment and can be reactivated by subsequent acid exposure, creating a cycle of ongoing inflammation and tissue injury. Recent research has identified pepsin deposits in laryngeal biopsies from patients with LPR, supporting the concept that enzymatic damage contributes significantly to symptom development. The presence of pepsin in laryngeal tissues helps explain why some patients continue to experience anterior neck pain despite adequate acid suppression, and why combination therapies targeting both acid production and pepsin activity may prove more effective in symptom resolution.

Nocturnal reflux events deserve particular attention as they often correlate strongly with anterior neck pain symptoms. During sleep, reduced saliva production, prolonged supine positioning, and decreased esophageal clearance mechanisms create optimal conditions for proximal acid migration. Patients frequently report waking with severe anterior neck pain, sore throat, and voice changes that may persist for several hours. Sleep position modification, including elevation of the head of the bed by 6-8 inches and avoidance of late evening meals, can significantly reduce nocturnal reflux events and associated anterior neck symptoms. Some patients benefit from prokinetic agents that enhance esophageal clearance and reduce the duration of acid contact with sensitive laryngeal tissues.