Clitoral pain represents one of the most distressing yet poorly understood aspects of female pelvic health, affecting countless individuals who often struggle to find adequate medical support or comprehensive information. This complex organ, containing over 8,000 nerve endings concentrated in an area smaller than a fingertip, can become a source of intense discomfort rather than pleasure when various pathological processes affect its delicate structures. Understanding the multifaceted nature of clitoral pain requires examining the intricate anatomy, diverse pathological mechanisms, and complex interplay between neurological, hormonal, and inflammatory factors that contribute to this challenging condition. Sharp, stabbing sensations in the clitoris can arise from numerous causes ranging from simple infections to complex neurological disorders, making accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment paramount for affected individuals seeking relief from this debilitating symptom.

Anatomical structure and innervation of the clitoris

The clitoris represents a remarkable feat of anatomical engineering, comprising far more than the visible glans that most people recognise. This complex organ extends deep into the pelvic cavity, forming a sophisticated structure of erectile tissue, nerve pathways, and vascular networks that work in concert to provide both sensory feedback and physiological responses. Understanding this intricate anatomy becomes crucial when investigating the various mechanisms that can produce sharp clitoral pain, as different components may be affected by distinct pathological processes.

Clitoral nerve pathways: dorsal clitoral nerve and pudendal nerve distribution

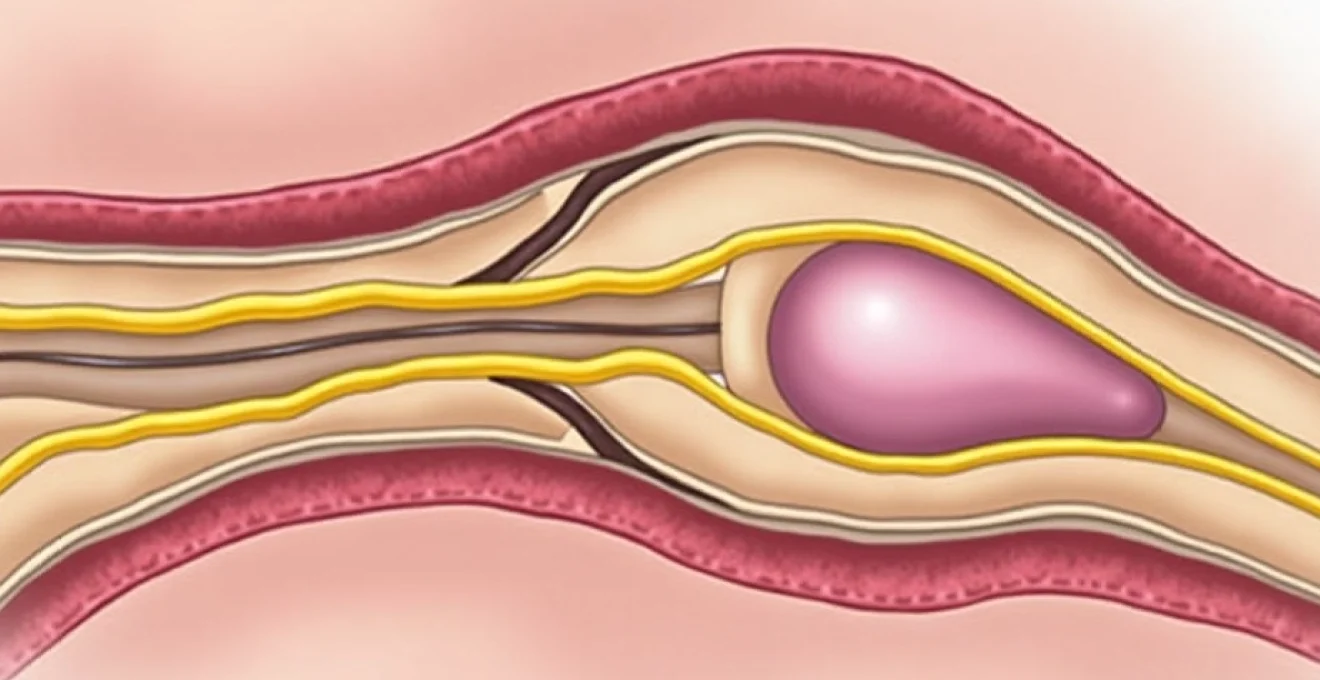

The sensory innervation of the clitoris primarily derives from the dorsal clitoral nerve, a terminal branch of the pudendal nerve that carries sensory information from the clitoral glans and surrounding tissues. This nerve pathway travels through the pudendal canal, also known as Alcock’s canal, where it can become susceptible to compression or irritation. The pudendal nerve itself originates from the sacral plexus, specifically from nerve roots S2-S4, making spinal pathology a potential contributor to clitoral pain syndromes.

Additionally, the clitoris receives sympathetic innervation from the hypogastric plexus and parasympathetic fibres from the pelvic splanchnic nerves. This complex neural network explains why clitoral pain can manifest in various patterns, from sharp, localised sensations to more diffuse, burning discomfort. Nerve entrapment at any point along these pathways can produce characteristic symptoms that help clinicians identify the underlying cause of the patient’s distress.

Vascular supply: clitoral artery and venous drainage mechanisms

The clitoral arterial supply stems from the internal pudendal artery, which gives rise to the clitoral artery before dividing into dorsal and deep branches. These vessels provide the necessary blood flow for normal clitoral function and tissue health. Vascular compromise, whether from trauma, inflammation, or systemic conditions affecting microcirculation, can lead to tissue hypoxia and subsequent pain.

Venous drainage follows a similar pattern, with clitoral veins eventually joining the internal pudendal venous system. Venous congestion or impaired drainage can contribute to clitoral engorgement and discomfort, particularly in conditions affecting pelvic floor muscle tension or during certain phases of the menstrual cycle when hormonal fluctuations influence vascular tone.

Erectile tissue composition: corpora cavernosa and glans sensitivity

The clitoral structure contains paired corpora cavernosa, similar to those found in the penis, composed of trabecular smooth muscle and endothelium-lined spaces that fill with blood during arousal. These erectile tissues extend well beyond the visible glans, forming the clitoral crura that anchor deep within the pelvic cavity. The glans itself represents the most densely innervated portion of the clitoris, making it particularly susceptible to painful sensations when inflammation or injury occurs.

The unique composition of clitoral erectile tissue makes it vulnerable to various pathological processes. Inflammatory conditions can cause swelling within these confined spaces, leading to pressure-related pain. Additionally, the high concentration of sensory receptors in the glans means that even minor irritation can produce disproportionately intense pain sensations.

Hormonal influence on clitoral tissue sensitivity

Hormonal fluctuations significantly impact clitoral tissue sensitivity and pain perception. Oestrogen levels directly influence the thickness and elasticity of clitoral tissues, whilst testosterone affects nerve sensitivity and arousal thresholds. During periods of hormonal transition, such as menopause or postpartum recovery, reduced oestrogen levels can lead to tissue atrophy and increased susceptibility to pain.

The cyclical nature of hormonal changes throughout the menstrual cycle can also influence clitoral sensitivity. Many individuals report varying degrees of clitoral discomfort or hypersensitivity at different points in their cycle, reflecting the dynamic relationship between hormonal status and neural function in this highly sensitive organ.

Inflammatory and infectious conditions causing clitoral pain

Infectious and inflammatory processes represent some of the most common causes of acute clitoral pain, often presenting with characteristic patterns that can aid in diagnosis. These conditions typically involve the vulvar tissues surrounding the clitoris, though direct involvement of clitoral structures can occur. The rich blood supply and warm, moist environment of the vulvar region create favourable conditions for various pathogens, whilst the delicate nature of clitoral tissues makes them particularly susceptible to inflammatory damage.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis: candida albicans impact on clitoral tissue

Vulvovaginal candidiasis, commonly known as thrush, frequently affects the clitoral region due to the proximity of infected vaginal tissues and the tendency for Candida albicans to proliferate in skin folds. The fungal infection produces intense itching and burning sensations that can extend to the clitoral hood and glans. Scratching in response to the intense pruritus can lead to secondary trauma and increased pain.

The inflammatory response triggered by candidal infection causes tissue swelling and increased sensitivity, making even light touch painful. Chronic or recurrent candidiasis can lead to persistent inflammation and altered pain perception, creating a cycle where the clitoral tissues remain hypersensitive even between active infections. Treatment requires not only antifungal therapy but also attention to predisposing factors such as diabetes, antibiotic use, or immunosuppression.

Bacterial vaginosis and clitoral inflammatory response

Bacterial vaginosis, characterised by an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria and a reduction in protective lactobacilli, can contribute to clitoral pain through several mechanisms. The altered vaginal pH and bacterial metabolites can irritate surrounding vulvar tissues, including the clitoral region. Additionally, the inflammatory cytokines released during bacterial vaginosis can sensitise nerve endings, lowering the pain threshold.

Unlike candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis typically produces less intense itching but may cause a burning sensation that extends to the clitoris, particularly during urination or sexual activity. The condition’s tendency to recur despite treatment can lead to chronic low-grade inflammation that maintains clitoral hypersensitivity over extended periods.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2: vesicular lesions on clitoral hood

Herpes simplex virus infections can directly affect clitoral structures, producing characteristic vesicular lesions on the clitoral hood or surrounding tissues. The initial outbreak typically presents with severe pain that may begin as a burning or tingling sensation before progressing to intense, sharp pain as vesicles form and rupture. The high concentration of nerve endings in the clitoral region makes herpes lesions in this area particularly painful.

The viral infection not only causes direct tissue damage but also triggers a robust inflammatory response that can affect nearby nerve pathways. Post-herpetic neuralgia represents a particularly troublesome complication where nerve damage from the initial infection leads to persistent pain long after the lesions have healed. This chronic pain syndrome can produce ongoing clitoral discomfort characterised by burning, shooting, or electric shock-like sensations.

Lichen sclerosus: autoimmune scarring and clitoral architecture changes

Lichen sclerosus represents a chronic inflammatory condition that can significantly impact clitoral anatomy and function. This autoimmune disorder causes progressive scarring and architectural changes that can lead to clitoral hood adhesions, reduced mobility, and altered sensation. The inflammatory process initially presents with white, parchment-like patches that may be accompanied by intense itching and pain.

As lichen sclerosus progresses, the scarring can physically distort clitoral structures, potentially burying the glans beneath thickened, inelastic tissue. This architectural change not only affects function but can also trap secretions and debris, leading to secondary infections and increased pain. The condition requires long-term management with topical corticosteroids and regular monitoring to prevent progression to more severe scarring or malignant transformation.

Neurological disorders and neuropathic clitoral pain

Neurological conditions affecting clitoral sensation represent some of the most challenging aspects of clitoral pain management, often producing symptoms that persist despite resolution of any apparent tissue pathology. These conditions involve dysfunction of the peripheral or central nervous system components responsible for clitoral sensation, leading to altered pain processing and hypersensitivity. Understanding the complex neurological pathways involved in clitoral sensation becomes essential when evaluating patients with persistent or unexplained clitoral pain, as these conditions often require specialised treatment approaches targeting the nervous system rather than local tissue factors.

Pudendal neuralgia: nerve entrapment syndrome affecting clitoral sensation

Pudendal neuralgia represents a chronic pain syndrome resulting from injury, inflammation, or entrapment of the pudendal nerve as it travels through the pelvic cavity. The condition can produce severe clitoral pain characterised by burning, shooting, or electric shock-like sensations that may worsen with sitting or physical activity. The pain often follows the anatomical distribution of the pudendal nerve, affecting not only the clitoris but also the perineum and anal region.

Several anatomical sites can contribute to pudendal nerve entrapment, including the sacrospinous ligament, the sacrotuberous ligament, and Alcock’s canal. Prolonged cycling, childbirth trauma, or pelvic surgery can predispose individuals to developing this condition. The diagnosis often proves challenging, requiring careful clinical assessment and sometimes specialised nerve conduction studies or diagnostic blocks to confirm the involvement of the pudendal nerve.

Clitoral hyperinnervation and allodynia mechanisms

Clitoral hyperinnervation and allodynia represent complex neurological phenomena where normal, non-painful stimuli become intensely painful. This condition can develop following trauma, infection, or as part of a broader pain syndrome affecting the vulvar region. The underlying mechanism involves sensitisation of nociceptors and altered central pain processing that amplifies normal sensory signals into painful experiences.

Allodynia in the clitoral region can be particularly distressing, as even light touch from clothing or gentle contact during intimate moments becomes unbearable. The condition often develops gradually, making it difficult for patients to identify a specific triggering event. Treatment typically requires a multimodal approach targeting both peripheral and central pain mechanisms through medications, topical treatments, and sometimes specialised neural blocks.

Post-herpetic neuralgia: chronic pain following genital herpes

Post-herpetic neuralgia affecting the clitoral region represents a particularly troublesome complication of herpes simplex virus infection. This condition develops when the initial viral infection causes lasting damage to nerve fibres, resulting in chronic pain that persists long after the acute infection has resolved. The pain typically presents as burning, shooting, or stabbing sensations that can be triggered by light touch or may occur spontaneously.

The development of post-herpetic neuralgia appears to be more common in older individuals and those with severe initial outbreaks. The damaged nerve fibres become hyperexcitable, sending abnormal pain signals to the brain even in the absence of ongoing tissue damage. Treatment often requires anticonvulsant medications or tricyclic antidepressants that can modulate nerve function and reduce the abnormal pain signalling.

Vulvodynia classification: generalised versus localised clitoral pain patterns

Vulvodynia represents a chronic pain condition affecting the vulvar region that can specifically involve clitoral structures. The condition is classified into generalised vulvodynia, which affects multiple areas of the vulva, and localised vulvodynia, which may specifically target the clitoral region. Clitorodynia , a subset of localised vulvodynia, produces persistent burning, stinging, or sharp pain specifically in the clitoral area.

The pathophysiology of vulvodynia involves complex interactions between inflammatory mediators, nerve sensitisation, and altered pain processing mechanisms. Genetic factors may predispose certain individuals to developing this condition, whilst environmental triggers such as infections, trauma, or hormonal changes can precipitate symptoms. The diagnosis remains one of exclusion, requiring careful evaluation to rule out other causes of clitoral pain before establishing this chronic pain syndrome as the underlying cause.

Hormonal fluctuations and clitoral pain correlation

Hormonal fluctuations exert profound effects on clitoral sensitivity and pain perception, creating cyclical patterns of discomfort that many individuals experience throughout their reproductive years and beyond. The intimate relationship between hormonal status and clitoral function reflects the complex interplay between oestrogen, testosterone, and other hormones in maintaining tissue health and neural function. These hormonal influences can dramatically alter pain thresholds, tissue sensitivity, and the body’s response to various stimuli affecting the clitoral region.

During the menstrual cycle, fluctuating hormone levels create predictable changes in clitoral sensitivity that can influence pain perception. The follicular phase, characterised by rising oestrogen levels, typically correlates with decreased pain sensitivity and improved tissue health. Conversely, the luteal phase and menstruation itself may be associated with increased clitoral sensitivity and heightened pain responses. These cyclical variations help explain why some individuals experience intermittent clitoral pain that follows their menstrual patterns.

Pregnancy and the postpartum period represent times of dramatic hormonal shifts that can significantly impact clitoral sensation and pain perception. During pregnancy, increased blood flow and tissue swelling can lead to heightened sensitivity, whilst the postpartum period’s sharp decline in oestrogen levels can produce tissue atrophy and increased pain sensitivity. Breastfeeding further extends this low-oestrogen state, potentially maintaining clitoral hypersensitivity for months after delivery.

Menopause represents perhaps the most significant hormonal transition affecting clitoral health, with declining oestrogen levels leading to tissue atrophy, reduced lubrication, and increased pain sensitivity. The gradual nature of this transition can make it difficult for individuals to recognise the hormonal basis of their increasing clitoral discomfort. Testosterone deficiency , which can occur independently or alongside oestrogen decline, further compounds these issues by affecting nerve sensitivity and arousal responses.

Hormonal contraceptives can also influence clitoral pain patterns, with some formulations reducing natural hormone production to levels that compromise tissue health and increase pain sensitivity. The synthetic hormones used in many contraceptive formulations may not adequately replicate the tissue-protective effects of naturally produced hormones, leaving some individuals more susceptible to clitoral pain and discomfort.

Mechanical trauma and physical injury to clitoral structures

Physical trauma to clitoral structures can occur through various mechanisms, ranging from accidental injury to complications from medical procedures or aggressive sexual activity. The delicate nature of clitoral tissues makes them particularly vulnerable to mechanical damage, whilst their rich nerve supply ensures that even minor injuries can produce disproportionately intense pain. Understanding the various types of trauma that can affect clitoral structures helps clinicians recognise injury patterns and implement appropriate treatment strategies.

Accidental trauma represents one common cause of acute clitoral pain, often occurring during activities such as cycling, horseback riding, or contact sports. The external location of clitoral structures makes them susceptible to direct impact injuries, which can cause bruising, swelling, and acute pain. Bicycle accidents, in particular, can produce significant trauma to the clitoral region when individuals fall forward onto the frame or handlebars. These injuries may cause immediate intense pain and can lead to lasting sensitivity if nerve damage occurs.

Medical procedures involving the vulvar region can occasionally result in inadvertent clitoral trauma, particularly during episiot

omy or vulvar biopsies. Surgical complications, though rare, can include inadvertent damage to clitoral nerve pathways or vascular structures, leading to persistent pain and altered sensation. Healthcare providers performing procedures in the vulvar region must exercise extreme care to avoid clitoral structures and minimise the risk of iatrogenic injury.

Sexual trauma represents a particularly sensitive but important cause of clitoral pain that requires careful consideration and empathetic management. Aggressive sexual activity, whether consensual or non-consensual, can cause tissue tears, bruising, or nerve damage that produces lasting pain and hypersensitivity. The psychological component of sexual trauma can compound physical injuries, creating complex pain syndromes that require multidisciplinary treatment approaches addressing both physical healing and emotional recovery.

Childbirth-related trauma can affect clitoral structures through various mechanisms, including direct pressure during delivery, episiotomy complications, or tears extending into the clitoral region. The intense pressure and stretching that occur during vaginal delivery can temporarily or permanently alter clitoral sensation, whilst instrumental deliveries using forceps or vacuum extraction may increase the risk of direct trauma to clitoral structures.

Repetitive microtrauma from activities such as aggressive masturbation or the use of poorly designed sex toys can gradually damage clitoral tissues, leading to chronic inflammation and pain. The cumulative effect of repeated minor injuries can sensitise nerve pathways and create lasting changes in pain perception, even when the original traumatic activities have ceased.

Diagnostic approaches for acute clitoral pain assessment

Diagnosing the underlying cause of acute clitoral pain requires a systematic approach that combines detailed history-taking, careful physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic testing. The intimate nature of clitoral pain complaints often makes patients reluctant to seek care or provide complete information, making the diagnostic process particularly challenging for healthcare providers. Establishing a comfortable, non-judgmental environment becomes crucial for obtaining accurate information and conducting necessary examinations.

The clinical history should explore the onset, character, and pattern of pain, including any relationship to menstrual cycles, sexual activity, or specific triggers. Healthcare providers must inquire about previous infections, trauma, surgical procedures, and medication use that might contribute to clitoral pain. The pain’s temporal pattern—whether constant, intermittent, or cyclical—can provide valuable diagnostic clues about underlying pathophysiology.

Physical examination of clitoral pain requires exceptional sensitivity and expertise, as the area’s high sensitivity can make examination itself painful for affected individuals. Visual inspection should assess for obvious lesions, inflammation, or anatomical abnormalities, whilst palpation must be performed with extreme gentleness to avoid exacerbating symptoms. The examination should include assessment of clitoral mobility, the presence of adhesions, and evaluation of surrounding vulvar tissues for signs of infection or dermatological conditions.

Cotton swab testing represents a valuable diagnostic tool for mapping areas of hypersensitivity and distinguishing between different types of vulvar pain. This technique involves gently touching various areas with a cotton-tipped applicator to identify specific regions of tenderness and characterise the pain response. The pattern of sensitivity can help differentiate between localised clitoral pain and more generalised vulvodynia.

Laboratory investigations may include vaginal swabs for bacterial and fungal cultures, testing for sexually transmitted infections, and assessment of vaginal pH and microscopy. Hormonal evaluation might be indicated in cases where hormonal deficiency is suspected, particularly in postmenopausal women or those with irregular menstrual cycles. Nerve conduction studies or specialised neurological assessments may be necessary when neuropathic pain is suspected.

Imaging studies typically play a limited role in clitoral pain evaluation, though magnetic resonance imaging might occasionally be useful for assessing deeper pelvic structures or identifying anatomical abnormalities. Ultrasound examination can sometimes reveal cystic lesions or assess blood flow to clitoral structures, though the technique’s utility remains limited in most cases of acute clitoral pain.

The diagnostic process often requires a multidisciplinary approach involving gynaecologists, dermatologists, neurologists, and pain specialists, depending on the suspected underlying cause. What strategies have you found most effective when seeking healthcare for intimate health concerns? The complexity of clitoral pain syndromes means that diagnosis may require multiple consultations and a process of elimination to identify the underlying cause accurately.

Differential diagnosis must consider the full spectrum of conditions that can produce clitoral pain, from simple infections to complex neurological disorders. The challenge lies in distinguishing between conditions that may present with similar symptoms but require vastly different treatment approaches. A systematic approach to differential diagnosis helps ensure that underlying causes are not missed and that appropriate treatment can be initiated promptly.

Documentation of findings becomes particularly important in clitoral pain cases, as symptoms may fluctuate over time and multiple healthcare providers may be involved in the patient’s care. Detailed records of examination findings, diagnostic test results, and treatment responses help build a comprehensive picture that guides ongoing management decisions and facilitates communication between different specialists involved in the patient’s care.