That familiar ache in the back of your arms following an intense training session isn’t just imagination—it’s a complex physiological response that reveals the intricate mechanisms governing muscle adaptation and recovery. Triceps pain after exercise represents one of the most common forms of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), affecting everyone from weekend warriors to elite athletes. Understanding why your triceps hurt after working out requires delving into the sophisticated interplay between muscle anatomy, cellular damage, and inflammatory responses that occur during the recovery process.

The triceps brachii, despite being a single muscle group, exhibits remarkable complexity in its response to training stress. This three-headed powerhouse undergoes significant mechanical and metabolic challenges during resistance exercise, leading to predictable patterns of discomfort that can persist for 24 to 72 hours post-workout. Exercise-induced muscle damage in the triceps involves multiple physiological pathways, from microscopic tears in muscle fibres to cascading inflammatory reactions that ultimately facilitate muscle growth and strength gains.

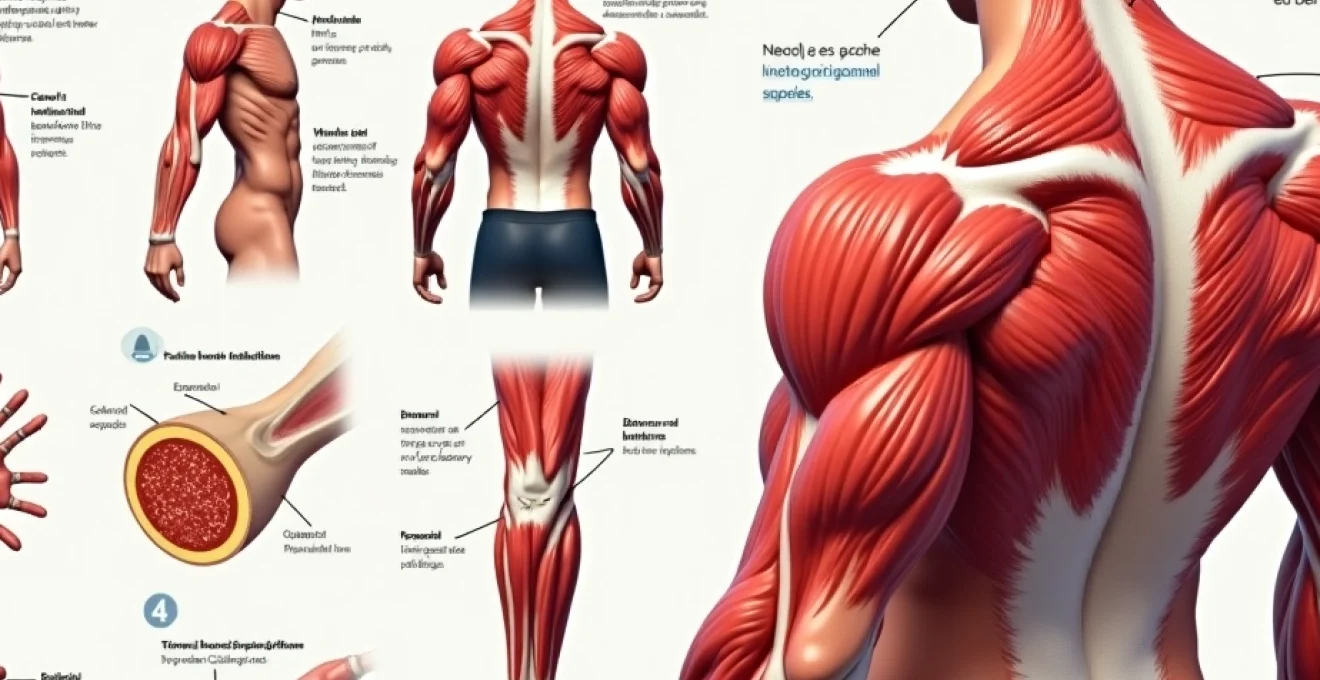

Anatomical structure and function of triceps brachii during exercise

The triceps brachii consists of three distinct heads—the long head, lateral head, and medial head—each contributing unique biomechanical properties to elbow extension and shoulder stability. This anatomical complexity directly influences how and why triceps pain manifests after training. The muscle’s primary insertion point at the olecranon process of the ulna creates a mechanical disadvantage that requires significant force production during resistance exercises, inherently predisposing the triceps to training-induced stress.

During compound movements like push-ups, bench presses, and overhead pressing variations, the triceps functions as both a primary mover and stabiliser. This dual role places considerable mechanical stress across all three heads, with varying degrees of activation depending on joint angles and movement patterns. The triceps’ role in decelerating the eccentric portion of movements—such as the lowering phase of a push-up—generates particularly high levels of mechanical tension that contribute to subsequent muscle soreness.

Long head triceps activation in overhead movements

The long head of the triceps originates from the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, making it the only head that crosses both the shoulder and elbow joints. This anatomical feature means overhead movements like military presses and triceps extensions place exceptional demands on the long head, often resulting in disproportionate soreness in this region. The stretch-shortening cycle experienced by the long head during overhead exercises creates optimal conditions for exercise-induced muscle damage, particularly when movements are performed through full range of motion.

Lateral head recruitment during Close-Grip pressing exercises

The lateral head demonstrates peak activation during close-grip pressing movements and triceps-specific exercises like skull crushers or close-grip bench press. Research indicates that the lateral head experiences the highest levels of mechanical stress during these exercises, correlating with increased post-exercise soreness in the outer portion of the triceps. The lateral head’s pennate muscle fibre arrangement creates high force-generating capacity but also increases susceptibility to micro-trauma during intense contractions.

Medial head stabilisation throughout range of motion

Often overlooked, the medial head provides crucial stabilisation throughout the entire range of triceps motion, remaining active across all joint angles. This continuous activation pattern means the medial head accumulates significant metabolic stress during high-volume training sessions. The deep location of the medial head can make soreness in this region feel particularly intense and difficult to address through conventional recovery methods.

Triceps insertion points and mechanical stress distribution

The convergence of all three triceps heads into a common tendon that inserts at the olecranon creates a focal point for mechanical stress concentration. During forceful elbow extension, this insertion point experiences forces that can exceed three times body weight, explaining why triceps tendon irritation often accompanies muscle soreness. The relatively small cross-sectional area of the triceps tendon compared to the muscle mass it serves creates a mechanical bottleneck that can contribute to delayed recovery and persistent discomfort.

Exercise-induced muscle damage mechanisms in triceps tissue

Understanding the cellular and molecular events that occur within triceps muscle fibres during and after exercise provides crucial insight into why pain develops and persists. Exercise-induced muscle damage represents a complex cascade of mechanical and metabolic stressors that trigger both immediate and delayed physiological responses. The triceps, with its high proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibres and significant force-generating capacity, is particularly susceptible to these damage mechanisms during resistance training.

The severity and duration of triceps pain directly correlate with the extent of muscle damage incurred during exercise. Factors such as training intensity, volume, exercise selection, and individual recovery capacity all influence the magnitude of damage and subsequent discomfort. Novel exercises or movement patterns that the triceps hasn’t adapted to typically produce more pronounced damage and longer-lasting soreness compared to familiar training stimuli.

Eccentric contraction phase and myofibril disruption

Eccentric contractions—where muscles lengthen under tension—generate the highest levels of mechanical stress and subsequent muscle damage in triceps tissue. During the lowering phase of pressing movements or the controlled descent in triceps extensions, individual muscle fibres experience forces that can exceed their structural capacity, leading to microscopic tears in the contractile proteins actin and myosin. These myofibril disruptions represent the primary mechanism underlying exercise-induced muscle damage and subsequent soreness.

Microtrauma formation in type II muscle fibres

The triceps contains a high percentage of Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibres, which are more susceptible to exercise-induced damage than their Type I counterparts. These powerful fibres generate significant force but lack the oxidative capacity and damage resistance of slow-twitch fibres. During high-intensity triceps training, Type II fibres experience preferential recruitment and subsequent microtrauma formation, explaining why power-based exercises often produce more pronounced soreness than endurance activities.

Creatine kinase release and cellular membrane permeability

Damaged muscle cells release intracellular enzymes like creatine kinase (CK) into the bloodstream, serving as biomarkers of muscle damage severity. Elevated CK levels following triceps training indicate compromised cellular membrane integrity and correlate with the intensity of muscle soreness experienced. Peak CK concentrations typically occur 24-48 hours after exercise, coinciding with maximum soreness levels and highlighting the delayed nature of exercise-induced muscle damage.

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) pathophysiology

DOMS in the triceps follows a predictable timeline, with soreness typically emerging 8-12 hours post-exercise and peaking between 24-72 hours. This delayed response reflects the time required for inflammatory mediators to accumulate and sensitise pain receptors within the muscle tissue. The characteristic stiffness and tenderness associated with triceps DOMS result from mechanical hyperalgesia —increased sensitivity to mechanical stimuli caused by inflammatory changes in the muscle environment.

Inflammatory response cascade following triceps training

The inflammatory response following triceps training represents a carefully orchestrated biological process designed to clear damaged tissue and initiate repair mechanisms. This complex cascade involves multiple cell types, signalling molecules, and physiological pathways that collectively produce the pain, swelling, and stiffness characteristic of post-exercise muscle soreness. Understanding these inflammatory mechanisms helps explain why triceps pain often feels worse 1-2 days after training rather than immediately following exercise.

The inflammatory response serves dual purposes: removing damaged cellular components and creating an optimal environment for muscle adaptation and growth. However, excessive or prolonged inflammation can impede recovery and contribute to persistent discomfort. The balance between beneficial and detrimental inflammatory responses depends largely on training load, recovery practices, and individual physiological factors that influence immune system reactivity.

Neutrophil infiltration and cytokine production

Within hours of intense triceps training, neutrophils—the body’s first-line immune defenders—migrate into damaged muscle tissue to begin the inflammatory response. These immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species that contribute to tissue breakdown and pain sensitisation. While neutrophil activity is essential for clearing damaged proteins and cellular debris, their presence also amplifies local inflammation and contributes to the characteristic soreness associated with exercise-induced muscle damage .

Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and pain signal transmission

Damaged triceps muscle cells and infiltrating immune cells produce prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a potent inflammatory mediator that directly sensitises pain receptors and amplifies discomfort signals. PGE2 production peaks 24-48 hours after exercise, coinciding with maximum soreness levels and explaining why triceps pain often feels most intense 1-2 days post-workout. This prostaglandin also increases vascular permeability, contributing to the swelling and stiffness that accompany muscle soreness.

Interleukin-6 release and systemic inflammatory markers

Intense triceps training triggers significant increases in interleukin-6 (IL-6), a multifunctional cytokine that orchestrates both local and systemic inflammatory responses. IL-6 levels can remain elevated for 24-72 hours following exercise, contributing to generalised feelings of fatigue and malaise that often accompany localised muscle soreness. This cytokine also plays crucial roles in muscle protein synthesis and adaptation, highlighting the dual nature of exercise-induced inflammation.

Exercise-induced inflammation represents a double-edged sword: while necessary for muscle adaptation and growth, excessive inflammatory responses can impede recovery and prolong discomfort.

Macrophage activation during muscle repair process

Following the initial neutrophil response, macrophages infiltrate damaged triceps tissue to continue the repair process. These specialised immune cells transition through different activation states, initially promoting inflammation and tissue breakdown before switching to anti-inflammatory and tissue-building functions. The timing and efficiency of this macrophage transition significantly influence recovery duration and the severity of persistent muscle soreness. Proper nutrition and recovery practices can optimise macrophage function and accelerate the resolution of triceps pain.

Common triceps training errors leading to excessive soreness

Many individuals unknowingly engage in training practices that exacerbate triceps soreness and prolong recovery times. Understanding these common errors can help you modify your approach to achieve optimal training benefits while minimising unnecessary discomfort. Progressive overload principles, proper exercise selection, and adequate recovery planning represent fundamental aspects of triceps training that, when mismanaged, often lead to excessive post-exercise pain.

The triceps’ involvement in numerous compound movements means that training errors can compound quickly, leading to cumulative stress that overwhelms the muscle’s recovery capacity. Poor exercise technique, inappropriate training frequencies, and inadequate attention to recovery needs represent the most frequent causes of problematic triceps soreness that extends beyond normal adaptation responses.

Training volume progression represents one of the most critical factors in managing post-exercise soreness. Rapid increases in training volume—whether through additional sets, repetitions, or training frequency—can overwhelm the triceps’ adaptive capacity and result in excessive muscle damage. Research suggests that training volume increases should not exceed 10-20% per week to allow adequate adaptation while minimising the risk of overreaching and prolonged soreness.

Exercise selection errors frequently contribute to disproportionate triceps soreness, particularly when individuals focus heavily on isolation exercises without adequate preparation or recovery. Movements that place the triceps in stretched positions under load—such as overhead triceps extensions or decline close-grip presses—generate higher levels of muscle damage and subsequent soreness. While these exercises can be valuable training tools, they require careful integration and appropriate progression to prevent excessive discomfort.

Inadequate warm-up protocols represent another significant contributor to triceps pain and injury risk. The triceps requires thorough preparation before intense training, including dynamic movements that progressively increase muscle temperature and activate all three heads. Jumping directly into heavy pressing movements or triceps-specific exercises without proper preparation increases mechanical stress and damage susceptibility, often resulting in more pronounced and longer-lasting soreness.

Proper exercise progression and adequate recovery planning represent the most effective strategies for managing triceps soreness while maintaining optimal training adaptations.

Training frequency errors—particularly insufficient recovery time between triceps-intensive sessions—can perpetuate soreness and impede adaptation. The triceps requires 48-72 hours for complete recovery from intense training, depending on individual factors and training intensity. Programming multiple triceps-heavy sessions within this recovery window prevents adequate tissue repair and can lead to cumulative damage that manifests as persistent soreness and declining performance.

Recovery protocols for triceps pain management

Effective triceps pain management requires a multi-faceted approach that addresses both the immediate discomfort and underlying physiological processes driving muscle soreness. Evidence-based recovery protocols can significantly reduce pain intensity and duration while supporting optimal adaptation responses. The key lies in understanding which interventions provide genuine therapeutic benefit versus those that merely mask symptoms without addressing underlying tissue damage and inflammation.

Active recovery represents one of the most effective strategies for managing triceps soreness while maintaining training momentum. Light movement and gentle stretching promote blood flow to damaged tissue, facilitating the removal of inflammatory mediators and delivery of nutrients essential for repair processes. However, the intensity and type of active recovery must be carefully calibrated to avoid additional muscle damage while providing therapeutic benefits.

Nutritional interventions play crucial roles in triceps recovery, with protein intake timing and quality significantly influencing repair rates and soreness resolution. Consuming 20-25 grams of high-quality protein within 2 hours post-exercise optimises muscle protein synthesis and can reduce the severity of subsequent soreness. Anti-inflammatory nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids, curcumin, and tart cherry compounds have demonstrated efficacy in reducing exercise-induced inflammation and associated discomfort.

- Cold water immersion (10-15°C for 10-15 minutes) within 2 hours post-exercise

- Contrast therapy alternating between heat and cold applications

- Gentle massage or self-myofascial release using foam rollers

- Adequate sleep (7-9 hours) to support growth hormone release and tissue repair

Sleep quality and duration represent often-overlooked factors in triceps recovery and soreness management. During deep sleep phases, the body releases growth hormone and other anabolic factors essential for muscle repair and adaptation. Poor sleep quality or insufficient duration can prolong inflammatory responses and extend recovery times, making adequate rest a non-negotiable component of any effective recovery protocol.

Hydration status significantly influences recovery processes and pain perception in damaged muscle tissue. Proper hydration supports lymphatic drainage of inflammatory mediators while maintaining optimal blood flow to recovering muscles. Aim for 35-40ml of fluid per kilogram of body weight daily, with additional intake during and after training sessions to replace losses and support recovery processes.

When triceps pain indicates potential injury or overtraining

While some degree of triceps soreness following intense training is normal and expected, certain pain characteristics and patterns may indicate more serious underlying issues requiring medical attention. Distinguishing between normal exercise-induced discomfort and potentially problematic pain requires careful attention to symptom onset, location, intensity, and duration. Understanding these warning signs can prevent minor issues from developing into significant injuries that require extended recovery periods.

Sharp, sudden-onset pain during exercise often indicates acute tissue damage that extends beyond normal exercise-induced muscle damage. This type of pain, particularly if accompanied by audible popping or tearing sensations, may suggest muscle strain or tendon injury requiring immediate assessment. Unlike the gradually developing soreness associated with normal training adaptations, acute injury pain typically manifests immediately and worsens with continued activity.

Persistent triceps pain that fails to improve within 72-96 hours or continues to worsen after this timeframe may indicate overtraining syndrome or chronic inflammation requiring intervention. Normal DOMS follows predictable patterns of onset and resolution, with pain typically peaking 24-48 hours post-exercise before gradually subsiding. Pain that persists beyond this normal timeline or continues to intensify may suggest inadequate recovery capacity or underlying inflammatory dysfunction.

Localised swelling, heat, or discoloration in the triceps region represents inflammatory responses that exceed normal post-exercise adaptations. While mild inflammation is expected following intense training, pronounced swelling or skin changes may indicate more significant tissue damage or compromised recovery processes. These symptoms warrant professional evaluation to rule out injury and develop appropriate treatment strategies.

Functional limitations that persist beyond the acute soreness phase may indicate injury or overtraining requiring intervention. Normal DOMS should not significantly impair daily activities or prevent basic arm movements once the initial 24-48 hour period has passed. Continued difficulty with

basic tasks like reaching overhead or pushing objects indicates dysfunction beyond normal exercise recovery.

Numbness, tingling, or radiating pain extending from the triceps into the forearm or hand suggests potential nerve involvement that requires professional evaluation. Exercise-induced muscle soreness should remain localised to the muscle belly and not involve neurological symptoms. Nerve compression or irritation can occur secondary to excessive swelling or improper exercise technique, particularly during overhead movements that place stress on the thoracic outlet or cubital tunnel regions.

Recognising the difference between normal exercise-induced discomfort and potentially serious injury symptoms can prevent minor issues from becoming chronic problems requiring extended rehabilitation.

Recurrent triceps pain that develops with minimal training stimulus may indicate chronic overuse syndrome or underlying biomechanical dysfunction requiring assessment and correction. Athletes who experience disproportionate soreness from routine training loads often demonstrate movement compensations or muscle imbalances that predispose them to excessive stress and delayed recovery. Professional movement analysis can identify these underlying issues and guide corrective interventions.

Systemic symptoms accompanying triceps pain—such as fever, generalised fatigue, or widespread muscle aches—may indicate more serious inflammatory conditions or infections requiring medical evaluation. While isolated muscle soreness is expected after training, systemic symptoms suggest broader physiological dysfunction that extends beyond normal exercise adaptations. These presentations warrant prompt medical assessment to rule out serious underlying conditions.

Temperature and colour changes in the triceps region that persist beyond 48 hours post-exercise may indicate compromised circulation or severe inflammatory responses requiring intervention. Normal post-exercise inflammation produces mild warmth and slight swelling that gradually resolves within 2-3 days. Persistent heat, significant swelling, or skin discoloration suggests inflammatory processes that exceed normal recovery capacity and may require anti-inflammatory interventions or medical evaluation.

Understanding when triceps pain represents normal adaptation versus potential pathology empowers individuals to make informed decisions about training modifications and medical consultation. The key lies in recognising patterns and characteristics that distinguish beneficial stress responses from potentially harmful inflammatory reactions. Early intervention for abnormal pain patterns can prevent progression to chronic conditions that require extensive rehabilitation and prolonged training modifications.